That’s Gandhi’s foot, above. More on that, below. But first: off to Little Italy.

To the Algebra Tea House on Murray Hill Road in Little Italy. You might call it “unique” or “original,” and these words are accurate but they understate the case to the point of insult. To call it a “labor of love” is also true, but the words fall flat in this glorious house of curves.

It’s a dream of a tea house. Tim Burton might create a movie set tea house that looked something like this. It would have all the wiggles and waves and off-kilter, expectation-jarring, surreal touches … but it wouldn’t be as inviting, as warm and cozy; it wouldn’t have a tenth of the friendliness. It wouldn’t have the unselfconscious grace. It also wouldn’t have the unevenness that charms, the earnest artistic attempts that just go a bit too far, and the genuine, child-like delight in creation. M. C. Escher might have sipped too much caffeine and imagined a place like this. But his etchings of the vision would have been black and white, harsh and angled, dry and sterile, cold.

Ayman Alkayali envisioned a coffee shop as a warm and welcoming neighborhood joint where the owner just happened to be very upfront about his Muslim faith. He wanted a cozy nook where people of all creeds and races could sit at the curving counter, sip espresso and talk freely, and get to know and like each other. He wanted to show the neighborhood that Islam was a warm and welcoming religion; nothing to fear. And so, while several decorations on the walls honor and explain Islam, while he is happy to talk about it when asked, there’s nothing proselytizing, nothing in-your-face, nothing to suggest any conflict among religions. He just wants you to see that Islam is a beautiful faith. That its essence is peace and love.

That’s a noble idea a coffee shop. It became a tea house because he couldn’t afford an espresso machine. Before he opened, while he worked days cooking in a nearby Italian restaurant, he spent two years renovating the abandoned bike shop. Most of his lumber came from two sources. He got all his Douglas fir beams from building tear-downs in Tremont. From Metro Hardwoods on the West Side, which rescues trees cut down by the city and bound for mulching or landfill, Alkayali got wood that he especially loved. You can see its struggles to grow in an urban environment: it’s knotty, uneven and full of odd bends and turns. One of his benches even had a bullet lodged in it. This wood has more character than forest or farmed wood, he says.

Then there are the other miscellaneous building and furniture materials: tree trunks, bricks, an old pot-belly stove, tin plate ceiling tiles, some aluminum sheeting instead of drywall, fabric remnants—he built the place out of serendipity, you might say. All with his own hands: every waving shelf and curving counter, every off-kilter mirror and neon squiggly ceramic floor tile, every Hobbit-shaped door and Dali-shaped vase, every driftwood door handle and multi-level table. There are some wonderful tables. The woodwork is simply gorgeous.

He also made every ceramic mug himself—pottery was his first love, as an artist. The mugs are a lot of fun. Not a simple cylinder shape in the place! And don’t expect standard serving sizes. Or that the saucers will fit underneath them. He did all the paintings. Creating this place from scratch took guts and demanded one hell of a gamble. His parents thought he was crazy. When Algebra Tea House opened, it was the first Muslim business in Little Italy.

Algebra Tea House opened in 2001, two weeks before September 11th.

There were some tough years.

It’s remarkable that the place survived. Alkayali worked two and three extra jobs to pay his tiny staff and keep the bank at bay. He didn’t get an espresso machine until 2003.

What enabled Alkayali to survive those first years? When hate was in the street, shouted in through the door? When hours crept by without a customer?

You might be tempted to think that only an iron will could keep going under such hardships. He did have to put up a fight against the city, after they tried to harass him out of business him with baseless inspections. But I think this is a side point: an element of the story, but not its center. More than anything else, I think the key is a radical innocence.

You see, to step inside Algebra Tea House is to step inside a mind. It’s not claustrophobic because it’s such a friendly and expansive mind. It’s utterly original, but at the same time unobtrusive. It’s a warm, accepting mind, a bold but gentle mind. It’s not an iron-willed, single-minded, blinkered mind. It’s a mind that when it sees an obstacle, bends.

Radical innocence is naïveté with a backbone. It is naïveté that doesn’t burn out. Alkayali was simply incapable of believing that the haters were truly hateful, that hate was the true contents of their hearts, that the customers wouldn’t come, and come to like it. Now, in 2018, Algebra Tea House is a Little Italy institution.

Alkayali told me that once, in an art class, the teacher asked him what school of art he followed. Unprepared for the question, he made up a term off the top of his head: curvism.

Wavy Thing #2: Cleveland Violins.

I first went into Cleveland Violins on the recommendation of my daughter’s violin teacher. That was many years ago, before I moved just three blocks away. It was love at first sight.

There’s something special about a violin workshop. I think it’s the combination of relentless exactitude and graceful bending. No, it’s the music. Any skillful mechanic or artisan knows exactitude and bending. But a violin shop is full of the most glorious music humans have ever achieved—even when it’s silent.

This shop on Mayfield Road is a Cleveland institution. It has the greatest endorsement possible: the world-class fiddlers of the Cleveland Orchestra drive up the hill from Severance Hall in their armored limousines, with their beefcake bodyguards tapping at earpieces to check in with the helicopters circling overhead, as they bring their Stradavarii here for oil change and repair.

That’s a slight exaggeration on my part. The guy at the desk tells me, “We’ve never actually had a Strad here.” He wouldn’t let me take any pictures of the interior, but told me I could lift some from the Facebook page. He explained that there are in fact only a handful artisans in America entrusted with those priceless Stradavarius violins, mostly in New York. But the world-class musicians of the Cleveland Orchestra and the Cleveland Institute of Music do carry their strings up the hill to be cared for in this music-monastic sanctuary.

What I love about the place is the glorious chaos of its window display—cascading waves of cello chassis—and the prodigal curviness of its décor: from the teeniest Suzuki violin to the stateliest, most sonorous, hollow-profound double bass: the tumult of tumbling pregnant bulges of gorgeous wood, and the overwhelming, uncompromising passion for stringed instruments.

Well, if I had a Stradavarius, this is where I’d bring it.

Wavy Thing #3: Gandhi’s Foot

My friend and co-teacher Roy Isaacs was born to an Indian immigrant father and European-American mother. His wife Shifa has India on both sides of her family and is third-generation Indian diaspora: born in Kenya, raised from age 11 in Wisconsin. They both want to pass on Indian culture to their children, and so it was natural for them a few years back to take their daughter and son to the statue of Mahatma Gandhi in the Cleveland Cultural Gardens to celebrate Gandhi’s birthday.

They had woven a mala, or garland, out of marigolds from a neighbor’s garden, and they intended to hang it around Gandhi’s neck in a traditional act of reverence for people who are alive or not, living or photographed or sculpted. But it’s a larger-than-life statue set on a one-foot rock that’s on a five-foot pedestal, and even the best Frisbee-shot couldn’t get the wreath on the target. So they settled for his foot. Roy points out that this is acceptable because honoring someone’s feet is actually the highest level of showing respect. Since Roy is six-foot-four it was within reach, and with its dynamic arc, that foot turned out to be a very satisfying perch.

The statue, by Gautam Pal, is the kind of work of art that would inspire reverence like that. Its dominant impression is that of motion. Gandhi is walking. And, it appears, at a pretty good clip. Roy tells me that the statue is in fact more specific than that. It’s Gandhi on the Salt March: a walk of 25 days in 1930 that launched the nonviolent Indian independence movement. Gandhi is, of course, scrawny and half naked. But this sculpture makes him a figure of pure energy, purpose and power. This little man is the breaking edge of a great human wave.

And he’s got a magnificent foot! It’s the best foot I’ve ever seen in a statue. I bet other statues look at it and think, “Why didn’t anyone tell me I could’ve worn sandals? Shoes are so boring! I didn’t know the human foot was so expressive!”

It’s a foot that conveys the dynamic forward motion of the whole work of art. And this is done through the powerful wave that surges out from the ankle, continues up the instep, and launches off into space with that spectacular big toe. If I ever meet Gautam Pal, I’m going to shake his hand and congratulate him for that toe. Never has a toe conveyed such character in a statue.

* * *

There are a few more locally wavy things I’d like to mention briefly. It will all make sense at the end. Three of them I plan to write about in future posts:

- The undulating roof of the Frank Gehry building on the campus of Case Western Reserve University

- The “Voyage of Life” in Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Wade Chapel at Lake View Cemetery

- The wonderfully imaginative and gently subversive annual festival of Parade the Circle at University Circle.

Also, another wavy thing is the land itself. I wrote about this in another post: the escarpment where the Appalachian Mountains give their last gasp before the flat lands of the lake.

* * *

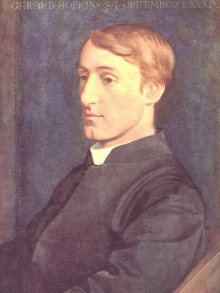

“Pied Beauty,” by the English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, is my inspiration for this blog post. The poem isn’t about wavy things, but spotted things. “Pied” here means multicolored (the Pied Piper wore such a costume). It’s a poem with its own radical innocence. “Why shouldn’t I write a poem about the beauty of spotted things!” he must have thought to himself. “Why not celebrate the mixed colors of the sky, the dappled cow, the stippled patterns on a fish?!”

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim …

And later in the poem he praises whatever combines the opposites: “swift and slow, sweet and sour, adazzle and dim.” And also: “All things counter, original, spare, strange.”

* * *

If lovely Father Gerard can praise spotted things, then why can’t I praise wavy things? So here’s my adaptation of that timeless poem, this time for the valleys of the Doan and Dugway.

Glory be to God for wavy things:

Algebra Tea House, Cleveland Violins,

For Gehry’s roof, a churning silver sea,

And Tiffany’s river of eternity.

Praise God for Gandhi’s foot, forever curled

In endless motion, over a curving world;

Parade the Circle’s undulating whimsy,

Old ladies on stilts, cavorting primly.

And for the land that breaks, and folds, and tumbles

Down to the lake. And for the wall that crumbles.

The ancient brick, its edges all ground down:

A traveler from another time, and town.

Beware the rigid dogmas, rational excesses,

The point that stabs, the angle that oppresses,

The tyranny of lines that never touch,

And carve the world for us and them so much.

Glory to the heart that bends and softens wisely,

The mind that opens imprecisely,

The lives that arc, however slightly,

The spirit that loves wildly.

Christopher Cotton